While a very recent or serious sprain may need a careful, special approach (see below), a ligament sprain which is older or not very serious can be one of the most simple injuries to resolve.[mfn]Mally J, “Multidirectional Friction”, downloaded on 27 Jun 2016 from Massage Technique Library[/mfn]

We are learning more about how the body responds to strains and sprains during the last 5 to 10 years, and this new research is changing the way we treat these tear injuries for the better – much better.

First of all, before we describe the treatment, let’s quickly cover off some important information.

What is a sprain?

“Sprain” is the term given to a tear of the fibres of ligaments or joint capsules – different to muscles.

A tear injury to a muscle or muscle tendon, is called a “strain.”

In summary:

- Tendons attach muscles to bones, and a tear injury is called a strain (or rupture).

- Ligaments attach bones to other bones, and a tear injury is called a sprain (or rupture).

- Joint capsules hold a joint together, and a tear injury is also called a sprain, since it makes up the capsular ligament.

- A similar tissue is a meniscus, such as those found in the knees or jaw. This can also be torn and is called simply a meniscal tear or rupture.

- Ruptures come in three flavours, or “grades.”

- Grade 1 is a slight tear, no big deal.

- Grade 2 is a partial tear, something like one-quarter of the thickness or more.

- Grade 3 is a complete rupture, where the whole structure has come unstuck.

Ligaments and joint capsules are made up of pretty much the same stuff: a very strong, collagen-based, cord-like structure, wrapped in fascia.

Ligaments change shape very little as you move since they must stabilise your joints and hold the bones in place, stopping them from going too far. They can bend and twist, but do not lengthen at all. They do not contract either and only shorten by going slack.

When you sprain a ligament or joint capsule your body responds with its immune system. Inflammation sparks off, and the injured area becomes red, swollen, hot, and painful. This is a natural, necessary, healthy response.

The suffix “~itis” is added to the name of the inflamed tissue, making the technical term for an inflamed ligament injury “ligamentitis.”

If it’s a joint capsule ligament that is inflamed, it’s called “capsulitis.” In some cases, there might be “adhesive” capsulitis.

If there are muscle-tendon strains as well as adhesive capsulitis, this is called a “frozen” joint such as frozen shoulder or frozen hip.

Be careful with fresh injuries

If you have injured a ligament within the last week, you’ll need to be careful with it.

DO NOT get a massage or any manual therapy directly onto a fresh sprain.

You can have the muscles around the injury massaged, but not the injury site itself.

If it’s a full-thickness tear, go to a doctor or physiotherapist.

If you aren’t sure whether it’s a full-thickness tear or not, call a doctor or physiotherapist on the phone and get some advice on what to do. They may ask you to come in to see them, or they may refer you for scans (usually ultrasound, possibly x-ray as well).

If you’re sure you just have a mild to moderate sprain, take it easy for a few weeks. Some movement will be fine but don’t push through pain or you might end up with either long-term ligament laxity or excessive stiffness.

You can ice it for the first day or two if that helps with pain, and you can take anti-inflammatory medication (like ibuprofen) if the pain is getting in the way of doing what you need to do in your day.

Be aware that ice and anti-inflammatory drugs can slow down the natural healing process of inflammation, so don’t keep up those remedies for more than a few days. After that, a warm wheat pack and careful, gentle movement are your best options.

Wait for at least a couple of weeks, and even then, your therapist will need to properly assess you and be careful not to re-injure you during treatment.

For fresh sprains, a massage should focus on relaxing the surrounding muscles so that they are not pulling on the sprain in dysfunctional ways. This will help the sprain to heal into healthy functional scar tissue.

Scar Tissue: Your friend now, your foe later.

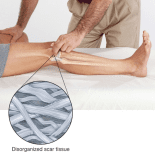

Your body responds to inflammation in ligaments and capsules by laying down lots and lots of collagen fibres in multi-directional orientations – a disorganised, interwoven, cross-thatched fashion (see the image in the first paragraph). This stabilises the site of injury to reduce the potential for re-injury. Your body then sends all the nourishment and building blocks needed to rebuild the injured tissue back to (hopefully) normal, functional tissue.

If all goes well and healing is healthy, your body will then break down any unnecessary extra collagen as the tissues rebuild. If unnecessary collagen remains, the site of injury will be restricted in movement.

After the initial healing process (usually about 2–6 weeks, called the ‘proliferative phase’), gentle movement of the injured area is necessary for that disorganised collagen scar tissue to re-organise itself into the correct, parallel orientation as you heal. Doing this is what informs your body which collagen fibres to break down and take away, and which to leave in place for further strengthening. The fibres kept in place will be organised and functional.

As the injury moves towards being fully healed (this can take between three and six months for a ligament sprain – this is called the ‘remodelling phase’) there should be normal movement with the ligament painlessly protecting your joint.

This is still technically scar tissue, but it is organised and functional healthy scar tissue rather than disorganised and dysfunctional unhealthy scar tissue.

The problem with disorganised scar tissue

If the scar tissue does not reorganise itself and stays disorganised, it can’t move, flex, or bear load correctly. The restricted (or excessive if lax) movement can cause pain. This pain may last for years after the initial injury has healed and may hold you back from living your life.

If there is no remaining heat, redness and swelling, and you feel pain only sometimes (that is, it’s only painful when irritated), then it cannot be called ligamentitis or capsulitis.

Remember, that “~itis” suffix means inflammation, and inflammation needs all of the features of heat, redness, swelling, and pain to be defined that way. Instead, it is more properly called ligamentosis or capsulosis, with the suffix “~osis” telling us that there is degeneration or damage to the tissues without inflammation. However, very few people (including health practitioners) actually use this word (which I think is weird, since it is accurate).

Whatever you call it, a persistent ligamentosis injury can still be a debilitating condition, making it hard to perform in sports and exercise or to do normal everyday activities without painful, annoying irritation.

Treatment

The treatment for such an injury is a relatively simple four-step protocol.[mfn]<a href=”http://aamt.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/james_waslaski.pdf”>”Pelvic Stabilization And Complicated Knee Conditions”</a> page 18, by James Waslaski of <a href=”http://www.orthomassage.net”>The Institute for Pain Management, Dallas, TX</a>[/mfn]

- Unload the muscles surrounding the injured joint so that they are not pulling on it and stressing the scarred fibres.

- Apply multi-directional friction with the pads of fingers or thumbs with no more than a moderate pressure for a maximum of 30 seconds. This softens the disorganised scar tissue.

- Compress the joint space to slacken the tissues, hold for a few seconds, and then suddenly release the joint to reorganise the softened fibres as they rebound and find tension again.

- Re-test for any pain on movement. If pain has increased, stop the treatment and try again the following day. If pain still occurs but is decreased, repeat the process up to three times, but no more as there is a risk of over-treating. Wait for another few days and try again.

If pain is significantly increased, stop this protocol and treat as you would an acute sprain and facilitate healing.

When successful, this process turns dysfunctional scar tissue into functional, pain-free scar tissue.[mfn]<a href=”http://aamt.com.au/wp-content/uploads/JW-ComplicatedKnee.pdf”>”Integrated Manual Therapy & Orthopedic Massage For Complicated Knee Conditions – Workshop Notes” page 11–12, by James Waslaski of <a href=”http://www.orthomassage.net”>The Institute for Pain Management, Dallas, TX</a>[/mfn]

It often amazes my clients when they find that the pain they had been living with for weeks, months or even years, having had old-fashioned or out-of-date treatments from other often very skilled therapists, simply goes away.

Sometimes it looks like magic. But I assure you, it’s just biology.

The problem with old-school treatments for sprains

One final word on the use of painful, aggressive traditional methods of treating sprains and strains.

Back when I was at massage college in 2007 we were taught that to re-organise the scar tissue we should apply cross-fibre frictioning to a deep level for up to six minutes and that this frictioning would realign the disorganised fibres.

What we now know from solid clinical research[mfn]Cook and Kahn, 1998 <a href=”http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1756121/pdf/v032p00346.pdf”>”Patellar tendinopathy: some aspects of basic science and clinical management”, Br J Sports Med 1998;32:346–355[/mfn] is that this approach actually further irritates and inflames the tissues, in some cases damaging the ligament or muscle-tendon even more than the original injury.

It is my opinion that this outdated method and its teaching must be replaced in the curriculum of manual therapy training centres immediately where it still exists.

If any therapist is making you ‘tap-out’ on the table due to the pain of treating a strain or sprain injury, seek another therapist who knows about these newer methods.

Sources:

- Mally J, “Multidirectional Friction”, downloaded on 27 Jun 2016 from Massage Technique Library.

- Waslaski J, 2012 “Pelvic Stabilization And Complicated Knee Conditions” p18, The Institute for Pain Management, Dallas, TX

- Waslaski J, 2012 “Integrated Manual Therapy & Orthopedic Massage For Complicated Knee Conditions – Workshop Notes” pp11–12, The Institute for Pain Management, Dallas, TX

- Cook and Kahn, 1998 “Patellar tendinopathy: some aspects of basic science and clinical management”, Br J Sports Med 1998;32:346–355