Remedial Massage for Chronic Muscle Pain and Central Nervous System (CNS) Sensitisation

Physical pain symptoms are the number one reason that patients seek healthcare in Australia at this time – more often than for infectious disease, cancer, or any other illness. Symptoms of pain are one of the primary reasons people take time off work. Pain also affects peoples’ abilities to take recreation, socialise with friends, and spend time with family. (Fillingim, et al., 2008)

Short term pain is one thing. Usually, we heal up and get over it pretty quick. A person experiencing chronic (ongoing) pain, however, tends to be more sensitive than normal to pain and touch. This condition of heightened sensitivity is called central nervous system (CNS) sensitisation or simply central sensitisation. (Baron et al., 2013)

In my experience, remedial massage can sometimes (but certainly not always) be an excellent part of lowering a person’s sensitivity to pain. I treated one person a few years ago who had a work-related back injury that led to a constant, general feeling of pain throughout their whole body. In the first one or two appointments, I could only very gently massage their body and limbs, as if I were slowly smoothing out a bedsheet.

Along with their medical treatments, and support from a counsellor, we were absolutely certain that the progressive remedial massage treatments helped to reset their brain’s ability to process physical touch. After about the fourth or fifth appointment, pain was localised to the site of original injury and only hurt on certain movements. Their partner told me they “felt like I got my life partner back again.”

Central sensitization and the central nervous system

We all experience pain when we are hurt or get sick. But have you ever noticed that different people seem to have different experiences of pain?

Our central nervous system encompasses the brain and spinal cord – the processing centres. So, CNS sensitisation means that the way we process pain signals increases sensitivity. (Baron et al., 2013) This is why some people have a higher pain tolerance and some lower even with the same stimulation. The stimulation may be the same but the way we process it is different.

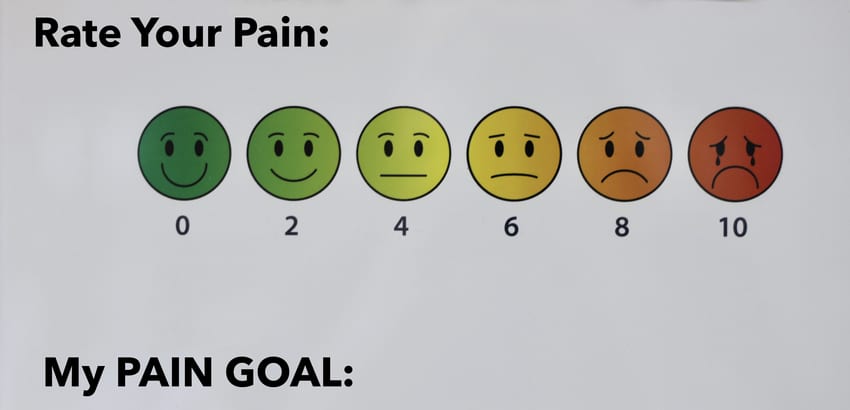

What this means is that the way we process pain can change. Our sensitivity can increase or decrease. So, the goal of therapy is to decrease sensitivity to a normal (or at least manageable) level.

How chronic pain happens

Chronic pain happens when there is a constant flow of warning signals within and between the brain and the spinal cord. With this constant signal, our mind decides that it must be important for us to experience the pain in order to avoid potential dangers.

We may still experience pain even after the healing of the initial injury has healed or the danger of reinjury has passed. (Vlaeyen et al., 1995)

Characteristics of CNS sensitisation

- Allodynia which occurs when a normal sensation becomes painful. In extreme cases, simply holding a fork or even a feather touching the skin can be excruciating.

- Hyperalgesia which occurs when a normal pain is now perceived as more painful than usual.

- Feelings of exaggerated pain even if the original causes are no longer present.

- Spreading pain sensations to normal tissues that are not injured.

(Moseley and Butler, 2013)

There are times when patients report having sensitivity to lights, sounds, and odours because their brain has developed a more general sensitivity as a result of the constant physical pain.

Sometimes sufferers also experience poor memory, concentration, and emotional distress. The person or their loved ones might think that they are going crazy because the sensations they can typically tolerate are now perceived as more painful.

Because there is constant pain, they might also feel increased anxiety with certain activities as they anticipate the possible pain that might occur. For example, putting a shirt on with overhead arm movements increasing shoulder pain. Simply dressing or bathing yourself can be very difficult!

It is very important to be kind, gentle, and patient with people experiencing chronic pain.

Consequences of CNS sensitisation

Chronic pain can potentially be a sign of, or lead to:

- rheumatoid arthritis

- osteoarthritis

- fibromyalgia

- temporomandibular disorders

- headache

- whiplash

- musculoskeletal disorders

- carpal tunnel syndrome; and

- postsurgical pain

(Chiarotto et al., 2013)

Causes of chronic muscle pain

The emotional connection

A typical injury or pain, even if it is infrequent, might be turned into frequent or chronic pain when thought and emotions become involved. (Moseley and Butler, 2013)

Chronic muscle pain usually happens when there is a consistent overworking or tension of muscles together with emotional trauma. This is why chronic muscle pain and CNS sensitisation are often associated with difficult jobs, traumatic accidents, or challenging life events.

But emotional trauma isn’t just about extreme causes, it can also be repetitive or irritating causes.

One example of emotional trauma is being afraid of what might happen when turning your arm in a particular direction following a mild shoulder sprain. You hold a subconscious memory of the muscles hurting when you turned your arm in that direction, and now it causes the brain to send out extra signals of pain in the muscle. The experience of this pain is still defined as emotional trauma, and now it is in a repeating pattern.

In the short term, this pattern served to protect you. However, our minds like to be efficient, and often hold on to repetitive response patterns even if they are no longer needed.

Links to diet and nutrition

Another theory behind chronic pain is nerve cell dysfunction. (Ji et al., 2013) When nerve cells send signals between each other, if the signals are disrupted in some way then the CNS will learn to adopt unusual communication patterns more widely. This can lead to too much sensitisation of pain receptors and signalling.

Nerve cell dysfunction may be caused by electrolyte imbalances including magnesium, calcium, or potassium, by dietary deficiencies, or chronic under-hydration. However, resolving this type of issue is not as simple as reintroducing these nutrients. Brain circuits take time to form, and also take time to un-form or be replaced.

The nutrients are crucial, but so, too, is bringing in regular mild-moderate exercise and, ideally, some kind of soft tissue therapy like remedial massage, shiatsu, or physiotherapy.

Physical damage, poisons, genetics, and psychosocial factors of pain

Structural damage from poisons or inflammatory disease as well as genetics can also play a role in the pain threshold of the patient. Interestingly, family upbringing, social relationships, and history of anxiety or depression can also have an influence on pain tolerance. (Fillingim, et al., 2008)

If you tend to have a high pain tolerance, it doesn’t make you better at being a human than someone else. It just means that in this one aspect, you have a different experience to someone with a lower tolerance. And you may simply be more plain lucky than others. Some people are better at swimming, some at running: we are all different.

How to treat chronic muscle pain and CNS sensitisation

There are chronic pain rehabilitation programs that use a combination of physical and cognitive therapies, and medications as part of the biopsychosocial model. (Gatchel, et al. 2014)

Medications such as antidepressants, muscle relaxants, and treatments like cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) are usually given to target the inflammation and pain symptoms involved in the CNS sensitisation.

Carers may also prescribe regular mild aerobic exercise to help ease the symptoms of chronic pain. Exercise has actually been known to reverse the effect of CNS sensitisation, especially if the pain involves the muscles.

Remedial Massage for CNS Sensitisation

An ordinary remedial massage might not be recommended to be given as it might cause more pain. We have to start from where the patient is, not where we think they should be, and work with them from there.

This kind of massage is about introducing touch in ways that the patient’s brain finds comfortable, tolerable, and hopefully enjoyable. With repeated treatments, their brain begins to anticipate and accept the enjoyable touch. Over time, this can reverse the cycle of increasing pain sensitivity, and begin to return things to normal.

Broad hands and sweeping strokes, not pokey fingers or thumbs, are the order of the day. After a few appointments, we can begin to gently and slowly knead and stretch the muscles and skin in ways that feel good to the patient, always staying within tolerable levels.

It can sometimes be challenging on the part of the practitioner as we may not initially be able to locate the original injury that causes the pain, either because the pain makes it impossible to assess the patient’s body, or because the injury has already healed. That’s why it is best to have a remedial massage therapy with an expert who is knowledgeable enough to address the CNS sensitisation first. Your expert therapist can also synch your remedial massages with the kinds of medical treatments mentioned above.

If you think I can help you with your chronic pain, send me an email or just hit the Book Me button!

Bibliography

Baron, R., Hans, G., & Dickenson, A. H. (2013). Peripheral input and its importance for central sensitization. Annals of Neurology, 74(5), 630–636. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.24017

Chiarotto, A., Fernandez-de-las-Peñas, C., Castaldo, M., & Villafañe, J. H. (2013). Bilateral Pressure Pain Hypersensitivity over the Hand as Potential Sign of Sensitization Mechanisms in Individuals with Thumb Carpometacarpal Osteoarthritis. Pain Medicine, 14(10), 1585–1592. https://doi.org/10.1111/pme.12179

Fillingim 1, R. B., Wallace, M. R., Herbstman, D. M., Ribeiro-Dasilva, M., & Staud, R. (2008, Nov). Genetic contributions to pain: a review of findings in humans. Oral Diseases, 14(8), 673-82. PubMed. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1601-0825.2008.01458.x

Gatchel, R. J., McGeary, D. D., McGeary, C. A., & Lippe, B. (2014). Interdisciplinary chronic pain management: Past, present, and future. American Psychologist, 69(2), 119–130. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035514

Ji, R.-R., Berta, T., & Nedergaard, M. (2013). Glia and pain: Is chronic pain a gliopathy? Pain, 154, S10–S28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2013.06.022

Moseley, G. L., Butler, D. S. (2013). Explain Pain. Cocos (Keeling) Islands: Noigroup Publications. https://www.noigroup.com/product/explain-pain-second-edition

Vlaeyen, J. W. S., Kole-Snijders, A. M. J., Rotteveel, A. M., Ruesink, R., & Heuts, P. H. T. G. (1995). The role of fear of movement/(re)injury in pain disability. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 5(4), 235–252. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02109988